Published by Zondervan on May 11, 2021

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Is religion a pernicious force in the world? Does it poison everything? Would we be better off without religion in general and Christianity in particular? Many skeptics certainly think so.

John Dickson has spent much of the last ten years reflecting on these difficult questions and on why so many doubters see Christianity as a major cause of harm not blessing. The skeptics, he concludes, are right: even a cursory look at the history of Christians reveals dark things therein--violence, bigotry, genocide, war, inquisition, oppression, imperialism, racism, corruption, greed, power, abuse. For centuries and even today, Christians have been among the worst bullies you could ever imagine.

But these skeptics are only partly right: this is not what Christianity was meant to be. When Christians do evil they are out of tune with the teachings of their Lord. Jesus gave the world a beautiful melody--of love, grace, charity, humility, non-violence, equality, human dignity--to which, tragically, his followers have more often than not been tone-deaf. Denying the evils of church history does not do. John Dickson gives an honest account of the mixed history of Christianity, the evil and the good. He concedes the Christians' complicity for centuries of bullying but also shows the myriad ways the beautiful melody of Christ has enriched our world and the lives of countless individuals. This book asks contemporary skeptics of religion to listen again to the melody of Jesus, despite the discord produced by too many Christians through history and today. It also leads contemporary believers into sober reflection on and repentance for their own participation in the tragic inconsistencies of Christendom and seeks to inspire them to live in tune with Christ.

Any time a book promises an “honest look” at anything, especially when it does so on its cover, the reader should immediately be on guard, because non-fiction, especially historical non-fiction, should be defined by its honesty. The tantalizing promise (or threat) of honesty has all the credibility of fishing tales’ common denominator, “I swear to God, it happened!”

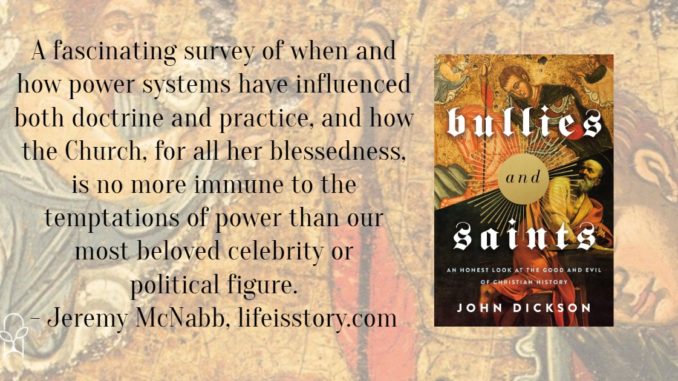

Pages of endorsements by reputable scholars of history, religion, and philosophy—people who are putting their reputation up as collateral on an author’s behalf—however, can indicate exactly the opposite. Oddly enough, John Dickson’s Bullies & Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History has both.

The prelude to the book introduces us to the author, as well as his surprisingly humble reflection on what used to be, for him, a robust confidence in the benefits that the Christian Church has brought to the world. A televised debate gone sour, some in-depth soul searching, and an honest reflection on Christian history gave John Dickson good cause to suspect that perhaps the world might have been better off without the Church.

The book’s format is simple: It is a survey of the best and worst moments of Christianity, weighed carefully, not in a manner where good works excuse bad, but where the roots of the good are examined alongside the roots of the bad. Dickson traces the Church’s tendency to comfortably hold hands with state authorities and empires, and at the same time, her contradictory tendency to be genuinely selfless when authoritarian support is absent.

Why do some Christians, even Christians a thousand years ago, value such seemingly modern concepts of equality, egalitarianism, pluralism, and consent, while others embrace a Christianity that looks like a baptized military conquest? The five Crusades, the Irish Troubles, and sexual abuse all seem to spring from the same fount as public hospitals and schools. Destruction and creation flowing from people bearing the same name.

From an anthropological perspective, Dickson has created a fascinating survey of when and how power systems have influenced both doctrine and practice, and how the Church, for all her blessedness, is no more immune to the temptations of power than our most beloved celebrity or political figure. From the Crusades to the Protestant Reformation, the link between power and perceived purity, has been a corrupting and tarnishing influence on the body of Christ in the world.

Dickson spends nearly three-hundred pages carefully weighing the evidence with such gravity that it would be impossible to reproduce his conclusions in a book review, and I wouldn’t want to spoil the read for anyone, anyway. The historical journey, the themes he teases out, and the consideration he gives to both historical context and to the lives of those who were affected is considerable, and definitely worth a read.