Published by Eerdmans on April 18, 2023

Genres: Academic, Non-Fiction, Christian Life, Politics, Theology

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear “evangelical”?

For many, the answer is “white,” “patriarchal,” “conservative,” or “fundamentalist”—but as Isaac B. Sharp reveals, the “big tent” of evangelicalism has historically been much bigger than we’ve been led to believe. In The Other Evangelicals, Sharp brings to light the stories of those twentieth-century evangelicals who didn’t fit the mold, including Black, feminist, progressive, and gay Christians.

Though the binary of fundamentalist evangelicals and modernist mainline Protestants is taken for granted today, Sharp demonstrates that fundamentalists and modernists battled over the title of “evangelical” in post–World War II America. In fact, many ideologies characteristic of evangelicalism today, such as “biblical womanhood” and political conservatism, arose only in reaction to the popularity of evangelical feminism and progressivism. Eventually, history was written by the “winners”—the Billy Grahams of American religion—while the “losers” were expelled from the movement via the establishment of institutions such as the National Association of Evangelicals.

Carefully researched and deftly written, The Other Evangelicals offers a breath of fresh air for scholars seeking a more inclusive history of religion in America.

I grew up proudly evangelical. Was trained at evangelical seminaries. Pastored at an evangelical church. But as time went on and the political underbelly of evangelicalism became more apparent to me, I was left with seemingly two choices: I could either walk away from it all or make a distinction between being politically and theologically evangelical. It was the late Ron Sider who helped me work through that distinction and my time spent with Christians Against Trumpism that kept me in the evangelical fold. I discovered that one could be evangelical but not That Kind of Evangelical. So then, The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians—and the Movement that Pushed Them Out, gave me an undiscovered history that helped me contextualize my place in evangelicalism and understand that I was not alone.

The Other Evangelicals is a reworking of Isaac Sharp’s dissertation for his Ph.D. in social ethics at Union Theological Seminary. As such, it is an inherently academic work that is comprehensive and has the references to prove it. Sharp divides the book into five chapters, each one covering the history of a particular marginalized group within evangelicalism: the liberals, the Black evangelicals, the progressives, the feminists, and the gay evangelicals. One weakness that I see in this is that the formatting prevents Sharp from easily discussing the intersectionality between these groups. However, Sharp is also progressing along a somewhat linear timeline. Evangelical and the liberals is focused on the 1940s-50s, Black evangelicals on the 60s, progressives on the 70s-80s, feminism gets scattered throughout the eras, and gay evangelicals are likewise scattered with discussing ending in the 21st century.

Each of these chapters could be a book in and of itself and indeed might have been better served as an expanded five-volume series, however ambitious that might have been. The Other Evangelicals is not meant to provide an exhaustive history but rather point to the major players and events that led to these minority groups being marginalized within evangelicalism. As much as there was, I found myself wanting more. In most areas, I found Sharp to be sufficient. The only chapter I felt needed more work was the final chapter on what Sharp calls “the gay evangelicals.” Even the use of that term belies a narrow focus and a failure to use the best language to describe LGBTQ+ Christians.

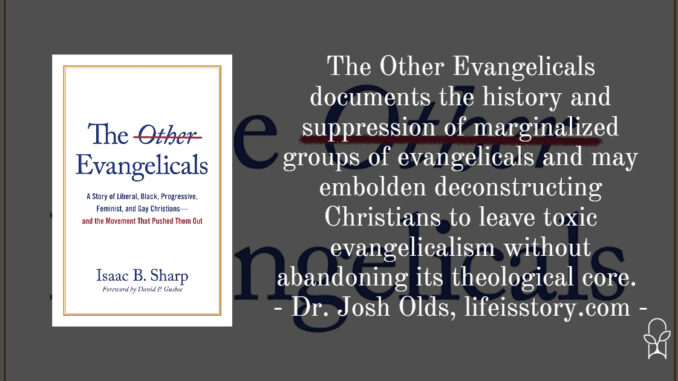

One the best things The Other Evangelicals does is present evangelicalism as a movement that got to where it is because of the major players within it desiring power. It contextualizes evangelicalism within the history of American politics and while it’s no Jesus and John Wayne, it does help set a more academic and expansive backdrop to it. This is an important book for evangelicalism. For some on the margins, it might make them stay and fight. For those outside evangelicalism, it helps trace the historical pathway to the present politicalization of the movement. Engaging and interesting, The Other Evangelicals allows readers to wonder what might have been and may embolden deconstructing Christians to tear away the toxicity of evangelicalism while retaining its theological core.