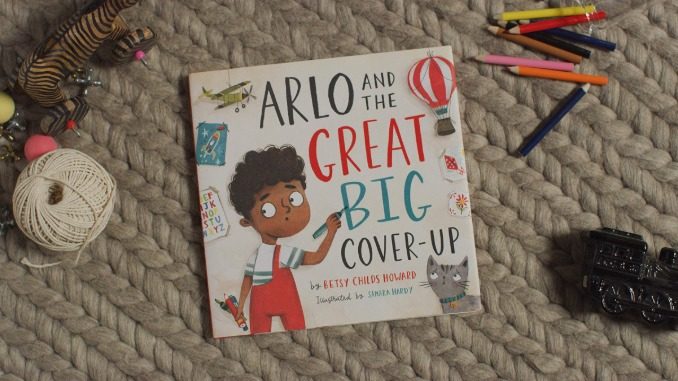

Published by Crossway Books on June 2, 2020

Genres: Children's

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Beautiful Illustrations - Simple Story - A Lesson on Repentance and Grace

Arlo knows better than to get out of bed during rest time. And he definitely isn't allowed to draw on the wall. But Arlo does it anyway, and then desperately attempts to cover up his disobedience before his mom finds out. When his efforts fail, Arlo discovers not only the misery that comes from hiding his sin but also the relief that comes through confessing it. With easy-to-understand language and engaging illustrations, children will learn important lessons with Arlo about repentance and the forgiveness found only in Jesus.

Arlo and the Great Big Cover-Up led to about an hour-long discussion on parenting between my wife and I. It’s a fairly standard premise in the “teach kids about sin and salvation” genre of children’s books. Kid does something he shouldn’t. Kid tries to hide the evidence of his wrongdoing. Kid fails. Parent finds out, helps them fix the wrongdoing, and gives them a consequence. It’s a paint-by-numbers just-for-children retelling of the Genesis 3 narrative of the Fall.

Arlo is having quiet rest time. He’s not supposed to get out of bed. But there’s a smudge just above his bed on the wall that looks like it could be a smile. With a marker, he could add some eyes…and it all devolves from there. It’s a workable analogy, but—and here’s the reason for the hour-long conversation between my wife and I—what is it teaching children about parenting?

Is there a reason that Arlo can’t get off his bed during quiet rest time? It doesn’t appear to be a naptime. Arlo seems older. The lights are on. It’s kind of weird that he’s not allowed to get out of bed. It seems to be there as a plot device simply to show how Arlo first finds a loophole in a rule (keeping one foot on the bed to reach the marker on the desk) before breaking a rule outright (writing on the wall). Reading with a child’s eyes, the impression I’d get of Arlo’s parents is that they’re very strict, or, at least, don’t understand what’s developmentally appropriate for their child.

Or, let’s look at a larger conception of the analogy: Arlo’s sin is in his disobedience to his parents and their rules. There’s nothing inherently sinful about getting off the bed. There’s nothing inherently sinful about drawing on the wall. Because Arlo’s indiscretions are against his parents primarily, and because this is an analogy of the Fall narrative, Arlo’s parents become a stand-in for God. That’s a dangerous thing to do in a children’s book. It leaves children with a far more authoritarian outlook on their parents than is warranted.

My wife and I talked about how we would handle a situation like this. Would we punish our son for writing on the walls? Well, first we would consider our own complicity in the situation. Did we contribute to the problem in any way? Yes, we allowed him to have markers unsupervised. That’s something we could have done differently to have avoided the situation. Second, we would try to understand our son’s motivations. Arlo is being creative—a hallmark of God’s image in him. We must make sure that he understands that creativity and impulsivity isn’t inherently a sin. (While, yes, acknowledging that many sins are the result of impulsivity.)

Third, we would recognize Arlo’s attempts to clean up his mess. It’s a good thing that Arlo, after his impulsivity had subsided, noticed his mistake and attempted to fix it. Our hope would be that, having failed to fix it, we could skip the cover-up and have our son come straight to us. This doesn’t align with the Fall narrative analogy, I understand, but this is the problem with the analogy: Parents are not God; children are not Adam and Eve—fully-formed adults without a sin nature.

So, in the end—Arlo and the Great Big Cover-Up is pretty standard and pretty much what I would expect. I don’t even think that I had worked through these parenting thoughts before reading this book. I was reading the book and the concept as an analogy. After reading it, and after discussion with my wife, we both came away from the book with the same feeling: We can read it as an analogy; our children won’t. And that affects how they think of us and how they think of God. Maybe I’m just overthinking a children’s book. Maybe it’s me. I certainly don’t blame Crossway or Betsy Childs Howard. This is a perfectly serviceable book and well within what I would expect. I have to give it good marks because it did everything it intended to do and did it exceptionally well. But this time, I began to wonder about the unintended consequences and wonder how we can do better.