Published by Eerdmans on September 14, 2021

Genres: Non-Fiction, Racial Reconciliation, Theology

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

A challenge to the doctrine of biblical inerrancy that calls into question how Christians are taught more about the way of Whiteness than the way of Jesus

Angela Parker wasn’t just trained to be a biblical scholar; she was trained to be a White male biblical scholar.

She is neither White nor male.

Dr. Parker’s experience of being taught to forsake her embodied identity in order to contort herself into the stifling construct of Whiteness is common among American Christians, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. This book calls the power structure behind this experience what it is: White supremacist authoritarianism.

Drawing from her perspective as a Womanist New Testament scholar, Dr. Parker describes how she learned to deconstruct one of White Christianity’s most pernicious lies: the conflation of biblical authority with the doctrines of inerrancy and infallibility. As Dr. Parker shows, these doctrines are less about the text of the Bible itself and more about the arbiters of its interpretation—historically, White males in positions of power who have used Scripture to justify control over marginalized groups.

This oppressive use of the Bible has been suffocating. To learn to breathe again, Dr. Parker says, we must “let God breathe in us.” We must read the Bible as authoritative, but not authoritarian. We must become conscious of the particularity of our identities, as we also become conscious of the particular identities of the biblical authors from whom we draw inspiration. And we must trust and remember that as long as God still breathes, we can too.

More so than any book in history, the Bible and its authority has been misused and weaponized to oppress and demean. From that foundation, Black womanist theologian Angela Parker embarks on an exploration of what biblical authority should actually mean and challenges the inherent biases often found within the doctrine of inerrancy.

I came to If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I? with some amount of skepticism. Growing up as a conservative evangelical, inerrancy and biblical authority were at the core of my theological education. I’ve shed much of that upbringing for a more liberal, yet-still-theologically-evangelical view, but inerrancy has been a tough one for me. I’ve come to understand how Scripture is often misused and misinterpreted—how people are errant—but I wasn’t sure about the step to questioning the actual inspiration of the Bible.

And while Parker doesn’t convince me entirely, what she does convince me of is how the doctrines of inerrancy and infallibility have been used to oppress and kill. Parker believes in biblical authority, but believes we need to question our relationship to Scripture and the way it has been used to promote White supremacy. She writes: “The underlying theme of this book is that our faith communities cannot fully breathe because White supremacist authoritarianism in the doctrines of inerrancy and infallibility have stifled God’s breath in us.”

The early chapters of the book detail Parker’s academic upbringing in White evangelical male culture—the default seminary culture for so many. Crucially, she shows how we can retain Biblical authority even while questioning interpretations and allowing for debate and discussion. The middle chapters give a few different example of the way in which traditional readings of Scripture have either devalued women or been used to center White authority and culture.

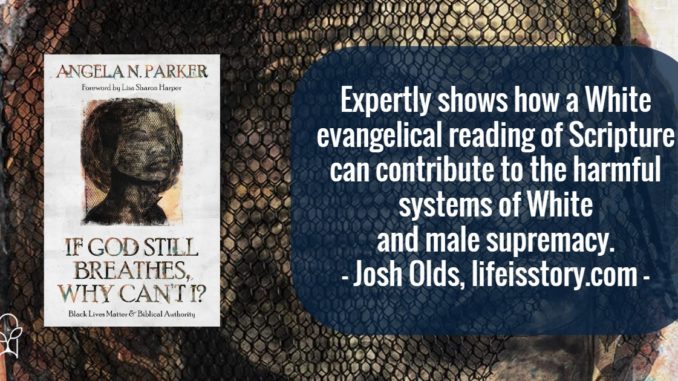

In the end, If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I? expertly shows how a White evangelical reading of Scripture can contribute to the harmful systems of White and male supremacy. However, I’m not at all convinced that we have to do away with the idea of inerrancy in order to correct this. Parker never, to my satisfaction, brings the two issues together. Whiteness-centered biblical scholarship is suffocating to people of color, and the doctrines of inerrancy and infallibility have been used as garrotes, but it’s not at all clear to me that the solution is to jettison inerrancy.

Rather, the solution might be that White supremacy has corrupted all doctrine and the solution is not to throw it away but redeem it. However, I can also acknowledge that somebody being strangled isn’t going to be to keen on being told “Well, you know, that’s really a useful tool you’re being strangled with when it’s used correctly.” Of course they’re going to want to get rid of it! Parker’s words are incisive, clear, and a bold word for (white, male) scholars like me who desperately need to glimpse a different perspective. That’s why I read this book, and I’m grateful for it.